SHET

SHET House Event Tunneling was a major home-automation project undertaken by myself alongside my house mates during the 2nd and 3rd years of undergrad. During those years we built a surprisingly comprehensive home automation system connecting to everything from the washing machine and lights to the house IRC channel.

The majority of the code is available on the house's GitHub page.

The rest of this document is a (still unfinished) write-up of what we did.

Introduction

This is the story of a group of Computer Science undergraduates and our quest to

avoid work at all costs by building a home

automation system for their

house. Its a tale of ridiculous hacks, novel architectures and, above all,

liberal use of blu-tack fun.

After meeting in our first year we decided we wanted to try and do something cool with our house. The resulting list of ideas was laughably ambitious, especially given that we couldn't really do anything to the building itself and that we also had to eat.

Two years and many hacks later and we have a remarkably feature-rich home automation system. We've got automated lights, media control, a washing machine that emails you, a recipe-browsing control panel, an electronic door-stop, a doop button and more! The whole thing is built on our own custom home automation system, 'SHET', and designed to be extremely hackable.

In The Beginning... (Motivation)

We started our grand plan listing off all manner of things we wanted our system to do. Apart from the slight concern of how we'd afford food after building this system, we also had to consider the wrath of the landlord. Whatever we built would have to be easily removed and not do (too much) damage to the house.

Our search for a house was a mixed affair. In the 3rd house with more mould than wallpaper, Tom was excited to discover one who's electricity meter had a light that flashed at a rate proportional to usage. Despite this critically important feature, we eventually decided to go somewhere else and landed up at 18 South Grove.

With our house found, we started thinking about what we wanted our home automation system to be like. Looking around the web we discovered that most systems were pretty bad. They generally were pretty clunky and seemingly designed for a bygone era or extremely limited and closed. We wanted something that was really flexible, hackable and actually nice to work with.

Seeing as we are all students, things were obviously going to have to be cheap. This ruled out a lot of options where specialist hardware was needed. Electronics knowledge (for all but Tom) was also in short supply which meant that the system would have to be electrically fairly simple. It also meant that high-voltage stuff was completely out of bounds.

SHET House Event Tunnelling (Designing the Software)

Our reaction to the problem of making the system hackable was a somewhat obvious one for any self-respecting *nix user:

"Shell scripts!"

- Jonathan

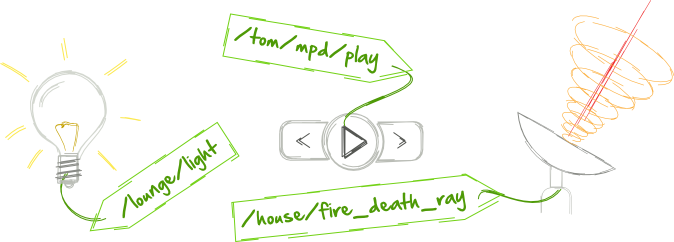

Luckily, sanity prevailed but the idea stuck. We decided that having a

file system-like tree containing all the controllable things in our

house was a cool way of doing things. For example,

/lounge/lights would control the lights in the lounge and

/jonathan/sound/speakers/volume would control the volume of

Jonathan's speakers.

With the idea of a 'file-system' full of real things, we set out to think about how this could work. We eventually settled with the idea that there would be three types of thing in the system:

- Properties

- For example, 'light' or 'volume'. These are values that can be got and set.

- Events

- For example, 'motion detected' or 'washing finished'. These are events that can be triggered by real-world or software events.

- Actions

- For example, 'close door', 'pause' or 'is washing machine in use'. These are a bit like function calls and can optionally take arguments and return values.

Unfortunately, this model doesn't really fit into a real file system and so the idea of using a FUSE file system to literally 'mount' our house was quickly abandoned. Instead we settled on producing a command-line utility and API for accessing the system.

Since the system was going to be house-wide it was going to need to run across a network. After looking around for libraries and protocols we could use to implement our system we eventually decided to write our own. Event-based systems existed but they were either far too enterprisey or too complicated. We also looked at using a standard RPC library but these once again proved overly complicated and lacked a reasonable way dealing with events.

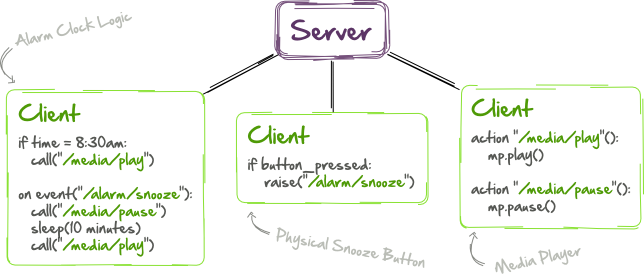

We decided on a centralised architecture with a single server and multiple clients. In our system the server would be pretty 'dumb' with all the application logic going on in the clients. The clients tell the server what nodes in the tree they contained and set/get properties, call actions or listen for events via the server that were created by other clients.

For example, we could have a client connected to light switches in the house, a client which monitored motion sensors and another client which listened for motion events from the second client and turned lights attached to the first on and off as needed. We could also run clients on our own computers to allow media players to be controlled over SHET.

Speed wasn't an issue seeing as this would be running on a LAN and so we focused our efforts on making the protocol simple human readable. After wrangling with some RPC frameworks and seeing how much hassle data types were, we decided we didn't want to deal with type-safety and so using JSON to encapsulate values in the system seemed like a good idea. From there it was obvious to use JSON to encode messages in the protocol too. After a late night on IRC Tom and Jonathan settled on what became known as the SHET protocol.

Unfortunately, as you might have guessed, the name is actually a backronym. From the IRC logs of SHET's conception:

(23:55:38) Jonathan: name for the protocol ?

(23:55:47) tomn: lol, no idea.

(23:56:00) Jonathan: karls: ideas?

(23:56:22) tomn: just string some buzwords together and acronym the hell out of

it :p

(23:57:10) Jonathan: :D

(23:57:30) Jonathan: take a list of rude or amusing words and swap the vowels

and then acronym the hell out of that

With the protocol designed, implementation was next on the list. Coursework deadlines loomed and so there was no time like the present and Tom set about writing the SHET Python API and SHET server using the Twisted framework. Twisted describes itself as "an event-driven networking engine written in Python" and provides a really nice API for implementing network protocols.

(TODO: Example client here)

As well as a Python API, a command-line utility was also made (complete with bash-completion). It allowed easy direct interaction with SHET and its servers. For example, you could browse through the tree with tab completion:

$ shet /jonathan/<tab> /jonathan/arduino/ /jonathan/irc/ /jonathan/sound/ /jonathan/desktop/ /jonathan/mpd/ /jonathan/tts/ /jonathan/email /jonathan/sms

Call actions (with arguments) and see their returned values:

$ shet /matt/mpd/toggle 0 $ shet /tom/sms "Let me know when you get in" null

Get and set properties:

$ shet /jonathan/sound/speakers/volume 100 $ shet /jonathan/sound/speakers/volume 21 null $ shet /jonathan/sound/speakers/volume 21

Watch events being raised:

$ shet /lounge/panel/pressed [6] [4] [1] ...

Of course, this interface meant that we could actually write shell scripts to control our house. For example, alarm clocks which could turn on lights and music could be created in seconds using a cron job.

After a while we got fed up of the command-line client being relatively slow (due to the overhead of starting Python). This (and further coursework deadlines) was all the motivation it took for Tom to write a C library for SHET and a command-line SHET client written in C.

The madness didn't stop here either as a JavaScript library appeared allowing us to build web interfaces trivially for any device. The library is built on Node.js and Socket.IO and is just as feature complete as the C and Python versions.

SHET-ify all the things! (Controlling Computers)

TODO: Talk about controlling

- MPD (Music Player Demon)

- SMS

- IRC

- Text-to-Speech

- Keyboard Bindings

- The 'bind' server.

SHETSource (Controlling Real-World Things)

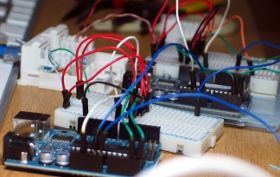

Right from the start, our aim was to control real things in our house like the lights. This meant having these things somehow connected to SHET. The answer we came up with was to use Arduinos thanks to their ease of use and off-the-shelf availability. They would allow us to run simple programs which controlled motors, switches, sensors, lights and anything else we could wire up around the house.

Of course, connecting these Arduinos to SHET posed a problem. Our first thought was that we might use an Ethernet shield and connect them all to our computer network. Unfortunately, the shields would be too expensive and since there would only be one network socket in each room, we'd have to buy lots of Ethernet switches too. We'd also need to power the Arduinos and their attached peripherals. Power-over-Ethernet was deemed too complicated and once again, too expensive.

After dismissing various bad ideas involving long USB cables and repeaters, Tom remembered that 10/100 Ethernet only uses four of the eight wires in a standard CAT-5 cable. As we didn't plan on using gigabit networking in our house, it meant we'd have four wires running from somewhere central in the house to every other room.

In order to use these unused wires, we had to make adapters which

split off the four Ethernet wires and the four spare wires at each end.

This meant re-writing the wall-sockets in each room and making adapters

for the cables in our comms electrical meter cupboard where

they were connected to the switch.

You might be wondering how common it is to find a full CAT-5 installation in a cheap student house and the answer is: not at all. When our very keen landlord offered to do "anything we could think of" while renovating the property we were pretty sceptical. A joking remark about fitting CAT-5 (and a plasma TV) were met with "sure" and we left not really thinking anything would happen. When he later contacted us to find out where we'd like the wall sockets we were pretty surprised.

So, with four wires available to us, this meant two for power and two for data (to keep things simple). Jonathan started experimenting with I2C, a simple data bus protocol, to connect the Arduinos together. There would be a 'master' Arduino connected to our server which would act as the interface between all the other Arduinos and SHET.

Despite our enthusiasm, we realised I2C really wasn't designed for long wires. After lots of head-scratching, continuity testing and fiddling with I2C settings Tom eventually found an I2C booster that might be the answer to our problems. A few days later and we wired up our shiny boosters and...it still didn't work.

At this point, we scrapped our plan of using I2C and instead started building a simple software serial library with basic flow control capabilities. To keep things simple, we decided to abandon the idea of using a bus and instead would connect the two data wires of each Arduino around the house directly into the otherwise unused pins of the master Arduino. The master would then route data to and from our server over USB.

Once again we connected everything up and...it worked! Now all we needed was a way of exposing all this to SHET.

After seeing the fairly dreadful performance of our serial link, we ditched any ideas about using the regular SHET protocol. Instead we considered a simple protocol which basically forwarded control of the IO pins back to our server. This idea seemed like an extremely wasteful use of Arduinos and so Jonathan set about designing a simple protocol which complemented SHET.

The idea was that each Arduino should be able to create events, properties and actions within SHET. These could be, for example, motion sensors, lights and buzzers. To keep things simple, it was decided that Arduinos would not be able to access other events, properties and actions within SHET, instead SHET clients would be written to fill the gap. This also forced us to keep our "application logic" off the Arduinos which would save lots of time constantly reprogramming them.

From this idea, SHETSource was born making it trivial to connect real-world things to SHET. Take a look at the following Arduino sketch which makes the internal LED controllable over SHET:

#include <pins.h> #include <comms.h> #include <SHETSource.h> /* Connect to SHETSource via pins 2 and 3. */ DirectPins pins = DirectPins(2,3); Comms comms = Comms(&pins); /* The SHETSource client. Set that by default, nodes are created in the * /arduino/ subdirectory in SHET. */ SHETSource::Client client = SHETSource::Client(&comms, "arduino"); /* Get the state of the LED */ int get_led(void) { return digitalRead(13); } /* Set the state of the LED */ void get_led(int state) { digitalWrite(13, state); } void setup() { client.Init(); /* Use the built-in LED */ pinMode(13, OUTPUT); /* Register a property for the LED in /arduino/led. */ client.AddProperty("led", set_led, get_led); } void loop() { /* Execute one iteration of the SHETSource mainloop. */ client.DoSHET(); }

For an embarrassingly long time, SHETSource sat in a state of being usable but somewhat unreliable due to a simple timing bug. With this fixed, everything ran smoothly until one day our electrical simplifications came back to bite us. After sitting down in the living room one day, Jonathan noticed various Arduinos were no longer responding. After chalking this up to yet another timing issue in the system, the problem sat ignored until later that evening when the affected Arduinos were found nice and toasty in their sockets. The cable carrying data and power to the Arduino in the lounge appeared to have shorted fairly badly taking out several Arduinos in the house. A binary search of the offending length of wire revealed a very poorly piece of cable trapped under a leg of the sofa.

After replacing the cable and AVRs, we still didn't feel motivated to put any proper electrical protection in place and instead carefully blu-tacked the cable out of the reach of the evil chair leg. (Thus solving the problem once and for all!)

TODO: Talk about later direct-USB and Bluetooth interfaces to Arduinos.

Let There Be Light (Control)!

One of the major things we wanted our system to do was to control lights around the house. Unfortunately, a sensible respect for high-voltages, our land-lord's property and our own wallets meant we weren't going to be able to do anything especially fancy. After being inspired by the most useless machine, Jonathan grabbed a servo motor, some trusty blu-tack and hacked the lights in his halls bedroom.

With this idea and a number of cheap (and apparently sand-lubricated) servos off ebay we gained control of almost all the lights around the house. Once again our shoddy electronics (and ridiculously long power wires) started causing us problems. When the servos were moved, they would stutter and nearby Arduinos would brown out. The solution was simply to add a nice meaty capacitor across the regulator that powered it.

Unfortunately, a couple of rooms (perhaps ironically, those of SHET's principle developers, Tom and Jonathan) were fitted with dimmer switches which weren't especially forthcoming to servo control. Many an idea involving 3D-printed gears and dismantled CD-ROM drives was conceived but still the lights remained rebelliously uncontrolled.

While Tom was browsing around Clas Ohlson he discovered some cheap, remote controlled wall sockets which looked like an ideal candidate for hacking. By hacking the remote, we would be able to control mains-voltage devices without touching anything high-voltage.

This store, incidentally, is the supplier of a bewildering selection of goods notably including what we've dubbed 'SHAT-5', the generic dual-twisted-pair cable SHETSource lives in after it leaves the safety of the CAT-5 wall sockets.

With a selection of individually controllable standalone lamps lighting Tom's room, the hack was declared a success. Such was their effectiveness that when a light fitting broke in our hallway, Christmas lights and a wireless socket were rigged up (in June) and set up in SHET as the hallway lights and normal (if a prematurely festive) service was resumed.

Unfortunately, Jonathan was still without controllable lighting. Tempted by Tom's discovery of relatively inexpensive LED strips, Jonathan ordered 5m of RGB LED strip with the hope of using it to light his room. Tom more sensibly opted for 5m of warm-white LEDs and we both waited as they made their way from China to our revision-worn hands.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, the RGB LED strip produced a cold, blue-white light which wasn't going to be ideal for standard room lighting. It did, however, prove pretty awesome when combined with Mattuliser, a music visualisation library Matt wrote.

What was surprising was just how bright and how pleasant the warm-white LEDs Tom bought were. Lengths were hung around his room and connected to his Arduino via some questionable ebay MOSFETs (with equally questionable heat sinks). The result was dimmable and very pleasant lighting and a further order of the same LED strip from Jonathan. A little while later and Jonathan's room too was bathed in glorious PWM'd light.

Who needs light switches anyway? (Automatic Lighting)

What use are computer controlled lighting without some sort of motion detection to automate turning lights on and off? The idea of hacking the burglar alarm's PIR?s (motion detectors) came up early on. Unfortunately we didn't want to annoy our landlord (or neighbours) by tampering with it directly and so settled with attaching an LDR (light sensor) over the flashing LED (so that's why they flash...).

Not every room had a PIR and so we turned again to ebay and bought some cheap PIR modules. When fed 5v, these modules simply provide a pulse easily read by an Arduino whenever they detect movement. Easy!

With controllable lights and motion sensors all over the house all we needed to do was quickly hack together a SHET client to "just do the obvious thing". Unfortunately, as with any human interface problem, it turned out this was going to be harder than we thought...

TODO: Story of the lighting server and the problem of trivially describing the "sensible" time to turn lights on and off.

The Button Panel (of Dreams and Nightmares)

Despite the fact that our system allowed us to automate many things, others would always require direct human interaction. One place in particular, our lounge & kitchen, required particular attention as there were plenty of opportunities for SHET control.

We search around the piles of miscellaneous buttons, dials and LEDs we had lying around and came up with an idea for a control panel. As there are five of us in the house, we wanted to have at least one button per person. For example, you could press a button and your playlist would be copied onto the computer in the lounge. In order to make the most of this small number of buttons, we wanted to allow chording (pressing more than one key at once) and long-pressing to squeeze more functions into the panel.

Despite the existence of theoretically up to 30 different actions, the system would be very arbitrary and unpleasant to use or learn. To make things clearer, we decided we'd add another button to allow multiple modes to be selected. For example, in a 'music' mode, you can easily control playback by pressing one of the five buttons or grab your playlist by pressing and holding 'your' button (as dictated by the alphabetical ordering of our names). In a 'washing machine reminder' mode, you could press your button to book a reminder and press-and-hold to clear it. To indicate what mode the panel was in, we added an RGB LED and each mode was allocated a colour.

Pressing the mode button would cycle through the different modes (giving a pleasing demo of the RGB LED...) and pressing the mode button along with one of the five main buttons a specific mode could be selected. This meant that we'd have only 5 modes and that wouldn't allow us to also have our own personalised modes. As a result, we added a second mode button which gave us each our own personal modes.

With all this talk of modes Matt, our resident Emacs user, was getting uncomfortable. We're also computer scientists and so the thought of being limited to only 300 actions seemed limiting. To improve the situation, a modifier key was added named the 'middle-switch'.

Surprisingly, this system proved reasonably easy to use, especially given that in essence it was a box with 8 anonymous buttons and an LED. Now that we had our system, we needed a way to bind key presses to things in SHET. Faced with this task, Jonathan set about creating panel-o-matic. It consists of a custom language for specifying button behaviours and a SHET client which takes button-press and mode-change events from the panel and sets properties or calls actions as appropriate. Here's an example of a configuration file.

MUSIC { // In music mode, pressing a button will trigger one of the following actions 0 => /lounge/mpd/prev; 1 => /lounge/mpd/next; 2 => /lounge/mpd/toggle; 3 => /lounge/amplifier/vol_dec 20; 4 => /lounge/amplifier/vol_inc 20; // Pressing the 'middle-switch' (modifier) and button 0 enables random mode ^0 => /lounge/mpd/random 1; // Pressing and holding with the middle-switch turns random mode off. _^0 => /lounge/mpd/random 0; // The _ indicates "holding down" a key, and the special "any(...)" syntax // allows any one of the listed keys to be pressed and the associated string // be passed to the action as an argument. _any(0 : "james" ,1 : "jonathan" ,2 : "karl" ,3 : "matt" ,4 : "tom") => /lounge/mpd/copy_playlist_from; }

With the panel finished, it was time to put it to work. The first and most obvious thing to do was allow control of MPD (the media player on our lounge computer). Since we already had an MPD SHET client, this simply required adding all the actions we wanted to the button panel configuration and took all of 5 minutes!

With a sensor on the washing machine and the SHET email-sending client, we had been setting up reminders by using the 'bind' client to set up a one-off binding that would cause the 'washing finished' notification to call the 'send email' action for the appropriate person. To allow bookings to be made and cancelled from the button panel, all we needed for each person was a panel-o-matic configuration along the lines of:

// Booking reminders with a press 0 => /bind/once /lounge/washing_machine/finished /james/email; // Cancelling reminders with a press-and-hold _0 => /bind/rm /lounge/washing_machine/finished /james/email;

Once again, a really useful feature implemented with a minimum of effort. As a finishing touch, we bound the "washing starting" event to change the panel to the reminder booking mode automatically.

Another feature we wanted was to be able to browse our house recipe website from the panel. Again, all we needed was to use the panel to trigger calls to the 'keybind' client on the lounge computer. As you can see from the video, the panel makes a surprisingly usable interface for browsing around from the other side of the kitchen.

We've also got a mode for interacting with IRC enabling requests for washing up and letting people know when dinner is ready.

We have one other miscellaneous mode which contains useful commands for interacting with the computer (such as close window). It also has a button which 'powers down' the room turning off music, screens and lights and turning on a light in the hallway.

The individual user modes have been fairly sparsely used in practice. They do however serve a few useful services. For example in Jonathan's mode there is a button which turns off his lights and music while copying his playlist into the lounge media player and launching the recipe browser. It also serves some less useful (but obviously more important services), for example, Matt's mode is an in-joke and meme sound-board.

Miscellaneous Hacks

TODO: Talk about:

- Touch panels

- Amplifier control

- Capacitative door handle sensing

- Oven monitoring

- Back door monitoring

- Electronic door stop

Wiring It Up

TODO: Talk about:

- Building an IO expander using an AVR

- Wiring the living room nicely

- Wiring conventions

- Complete IO listing of the house (for fun!)

Getting Started (Downloads & Docs)

We think SHET is a really cool base for hackable home automation systems. If you're interested in trying it out yourself then here's a few links you might want to get started. SHET and SHETSource are currently moderately well documented and fairly stable so you should be able to get going without too much difficulty.

As you might imagine, a lot of the clients we've written are very specific to our house's setup and quickly hacked together to scratch an itch. They also come with an embarrassing quantity of documentation but hopefully should be occasionally useful.

- Our Libraries

-

- SHET: https://github.com/18sg/SHET

- SHETC: https://github.com/18sg/SHETC

- shet-client.js: https://github.com/18sg/shet-client.js

- SHETSource: https://github.com/18sg/SHETSource

- Example SHET & SHETSource Clients

-

- Command-line Interface: https://github.com/18sg/SHETCClient

- Lighting Server: https://github.com/18sg/SHETLights

- SHET IRC Bot: https://github.com/18sg/SHETBot

- Lounge Panel Client: https://github.com/18sg/Panel-O-Matic-SHET-Client

- Random SHET Clients: https://github.com/18sg/Random-SHET-Clients

- Random SHETSource Clients:

- https://github.com/18sg/Random-SHETSource-Clients

- Built With

-

- Twisted: http://twistedmatrix.com/

- Arduino: http://arduino.cc/

- Node.js: http://nodejs.org/

- Socket.io: http://socket.io/

- Find Us on Github

-

- Our (18sg) Github: https://github.com/18sg

- Amanieu's Github: https://github.com/amanieu

- James' Github: https://github.com/j616

- Jonathan's Github: https://github.com/mossblaser

- Karl's Github: https://github.com/karls

- Matt's Github: https://github.com/matty3269

- Tom's Github: https://github.com/tomjnixon

Copyright

SHET was the result of lots of interesting discussions, many hours of hard work and nights spent being kept up by malfunctioning servos. We believe that everyone should benefit from the fun we've had and so the whole project is open source.

© 18sg/The University House Guys 2012

This write-up is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.