Mesh Muddling Madness1

The theory of six degrees of separation is the idea that any living person is only six introductions away. In other words, the graph with nodes being people and edges being their friendships has a very low maximum-shortest-path-length (or diameter) compared to the number of nodes. Networks such as these are known as 'small-world networks' and this article explores what properties a super-computer wired up in this manner might have.

Making Small-World Networks

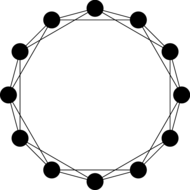

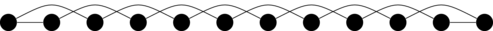

Watts and Strogatz proposed an

algorithm for generating

random small-world networks. The algorithm starts with a ring network of

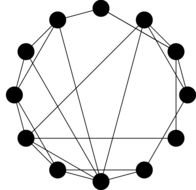

To turn this network into a small-world network, a small percentage of the edges

are randomly re-wired2. In the example below, edges are rewired

with a probability

The modified graph now exhibits various small-world properties, notably a reduced average path-length.

Making Small-World Super-Computers

For certain computing tasks reducing the average path-length in the network may

be desirable as it would potentially reduce the latency between arbitrary pairs

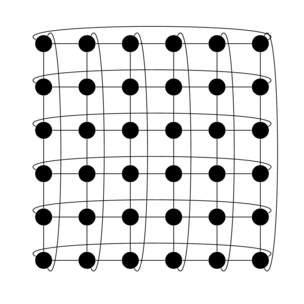

of nodes in the system. Super-computer interconnection systems tend not to use

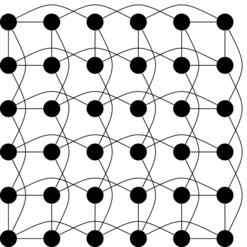

ring networks but instead a

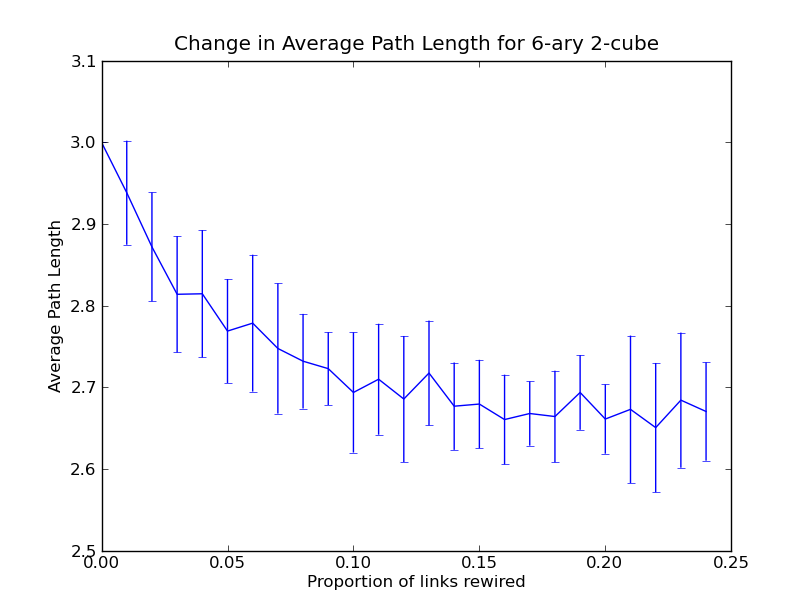

The network above is a 2D torus (a 6-ary 2-cube), in this network the average

path length (in terms of hops) is

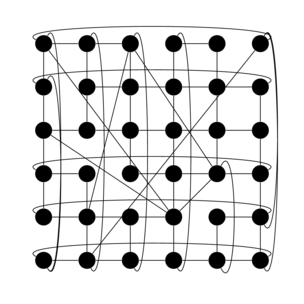

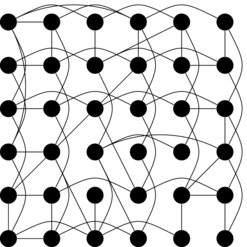

If the network shown above has been rewired with

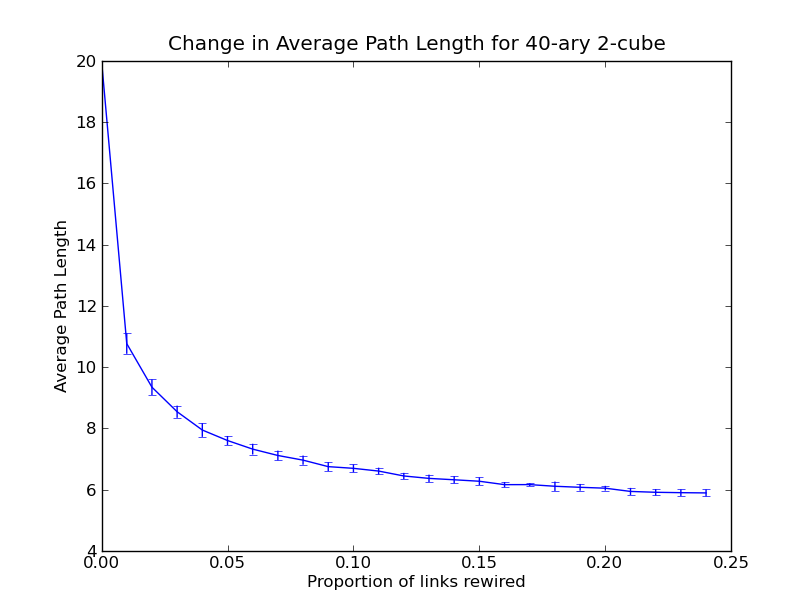

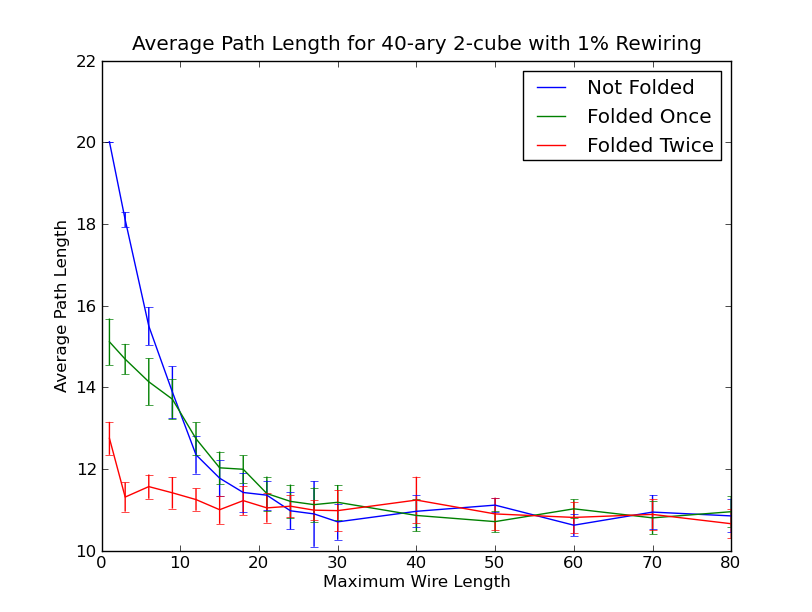

With larger networks the effect becomes more significant. Below shows the results for a 40-ary 2-cube4. Here the average path length drops by almost 50% when just 1% of edges are rewired.

Practical Wiring

Unfortunately, adding wires at random like we have done in the previous examples could be problematic for real-world systems. It isn't practical to have wires above a certain length and when laid out naively as shown above you can see that long wires crossing the whole system appear.

Folding Long Wires

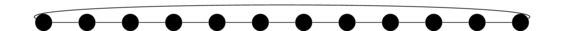

In order to keep wire-lengths manageable, the whole network should be folded in half. For example, this ring network:

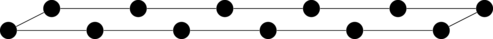

Can be folded in half to yield this arrangement containing no wires which cross the whole system:

Or, drawn flattened:

This process can be generalised to minimise the maximum wire-length required for 2-cubes as well:

Keeping Randomly-Created Wires Short

Of course, things start to get interesting when we start rewiring the edges as

long wires can start to reappear. For example, here is the same network with

rewiring of edges with

As you can see there are several long wires including one that crosses nearly the longest jump in the system (bottom left to nearly-top right).

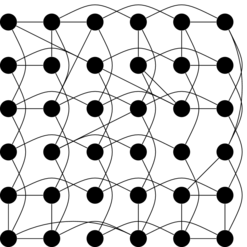

In an attempt to combat this problem we can change the rewiring algorithm to only create new links whose links are relatively short.

The rewiring above constrains the maximum wire to be 3 units long (where a unit is the spacing between each node in a given dimension). We still see that the maximum path length still drops, this time to 2.73, but now there are no long wires.

To test the effects of limiting wire lengths when re-wiring, a parameter sweep was carried out for a 40-ary 2-cube both with and without folding:

For very short wire length limits, folding provides improved average path-lengths, presumably because it is better-able to insert links to nodes topologically far away using only short wires. This is due to the fact that each folding moves the furthest nodes much closer at the expense of slightly increasing the wire length between topologically close nodes.

The other interesting effect visible in the graph is that allowing wires longer

than about 25 units has no significant effect on the average path length. I

hypothesise that there is some small benefit hidden by noise) which eventually

disappears when wires reach 40 units long. This is due to the fact that wires of

a maximum length of 40 allow packets to jump beyond the length of the maximum

shortest-path possible in the system which would never be useful: a wire which

travels the equivalent distance of

Remaining Work

Much work remains to be done in this analysis. In particular:

- A formula which calculates the expected average path length in the case of rewiring and wire-length limited rewiring.

- An analysis of the use of edge-adding variation on the Watts Strogatz model

- An analysis of how this effects the bisection-bandwidth of the network

- An analysis of routing challenges

-

This piece could alternatively be titled "Torus Twiddling Tedium", depending on your level of enthusiasm. ↩

-

In Watts and Strogatz's original algorithm it is also defined that the random re-wirings shouldn't create self-loops or duplicate edges. ↩

-

The ring network shown in the first example can be described as a 12-ary 1-cube. ↩

-

Because a 40-ary 2 cube relatively slow to exhaustively search many times (and I'm impatient), the average path lengths in that experiment were calculated by sampling from 10 random starting nodes. ↩